Sharetribe becomes a democratically governed company

At Sharetribe, the highest decision-making power is held by team members, based on the principle of one person, one vote.

Oct 30, 2025

At Sharetribe, we put a lot of thought into ensuring our company remains a net positive force in society. One of our values is "purpose before profit": our company exists to democratize platform ownership, and our profits are a means to achieve this end. We want to ensure this will always remain so.

In 2018, we transitioned from a traditional startup structure to steward-ownership, which ensures that the company will always be controlled by its team, not by outside investors. It also introduced caps on the returns that team members and investors can receive from the company's profits.

In this transition, one area was left unchanged: the actual distribution of voting power within the team. In the years that followed, my co-founder Antti and I held the majority of the voting shares and remained effectively in a dictatorial position. There was no way for anyone to hold us accountable. We knew the right next step would be to change this.

The remaining step has now been completed. As of June 2025, Sharetribe is democratically governed based on the principle of one person, one vote. Anyone who has been part of our team for at least two years can apply to become a steward. After completing steward training, they will get a voting share. Nobody, myself included, can hold more than one voting share. In June, 19 out of our 21 current team members were eligible to apply, and they all became stewards and received their voting shares.

This group of stewards now holds the highest decision-making power at Sharetribe. If more than 50% of them believe that I'm doing a bad job as the CEO, they can ask me to leave.

Why democratic governance?

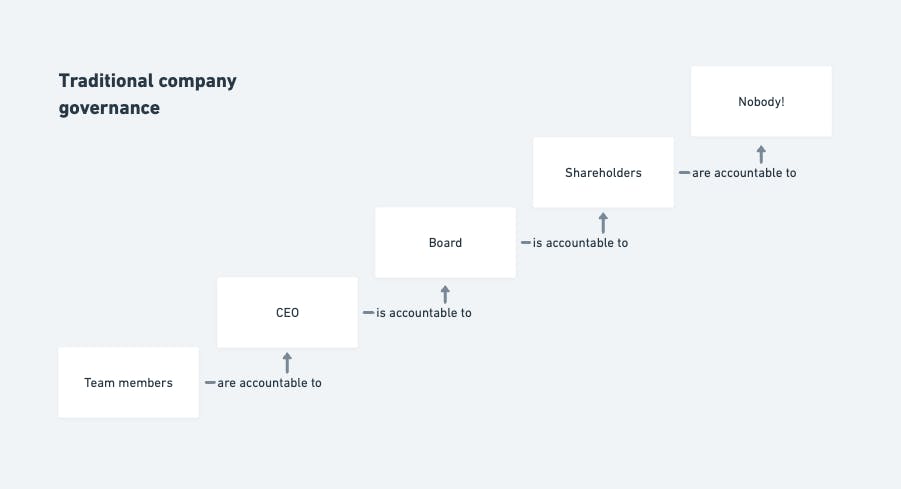

In a traditional company, accountability works as shown in the diagram below.

The team members, at the bottom, are accountable to the CEO. The CEO, in turn, is accountable to the board. The board is accountable to the shareholders.

How about the shareholders? They aren’t accountable to anyone! They can decide against the interests of team members or maximize their own profits at the cost of the company's mission, the environment, or society at large. The only limit to their power is laws and regulations, which always lag behind.

Many tech CEOs are unhappy with their position in this diagram. As a result, many have taken steps to move themselves to the top. For example, Mark Zuckerberg currently holds 53% of the voting power of Facebook’s parent company Meta, giving him full control. But this "benevolent dictator" approach doesn’t tend to lead to good outcomes, either. Meta’s net effect on society is negative, according to the Upright Project’s data model.

In fact, there are numerous examples of founder-controlled companies going astray. (The phenomenon is so well known it has a name: “Founderitis” or “Founder’s syndrome”). Two recent ones come from companies I've followed and admired for a long time: 37signals (makers of Basecamp) and Automattic (stewards of WordPress). 37signals's founders were unable to deal with their team's growing demands for diversity, equity and inclusion, which resulted in a third of the team leaving. Automattic founder Matt Mullenweg dealt damage to the open-source community by going after WP Engine in a questionable manner, again resulting in a large part of the team leaving.

As Lord Acton famously said: "Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely."

Steward-owned companies try to remedy these issues by separating money and power: the stewards might still be dictators, but they can't use their power to put money into their own pockets. I believe this helps a lot, but I'm not sure it goes far enough.

Patagonia is a steward-owned company, but its founders retain significant control, and it hasn't always acted in its team's best interests. Bosch is a steward-owned company led by a group of 10 stewards, and it contributed to the Volkswagen emissions scandal by manufacturing the device used in the scam.

Elon Musk buying Twitter and using it to advance his own political agenda is a good example of a situation in which a dictator's actions don't seem motivated by financial gain. Every person has their own biases, and without checks and balances to curb the dictator’s power, those biases are amplified in ways that are not optimal for society at large.

A third common approach to organizational governance is the democratic governance of cooperatives. Their challenge is that democratic decision-making is slow: cooperatives often adapt to change more slowly than traditional companies. And unlike steward-owned companies, they lack a mechanism for making sure the interest of their members align with the interest of society as a whole.

When designing Sharetribe's governance system, we concluded that we need to combine ideas from traditional companies, steward-ownership, and cooperatives.

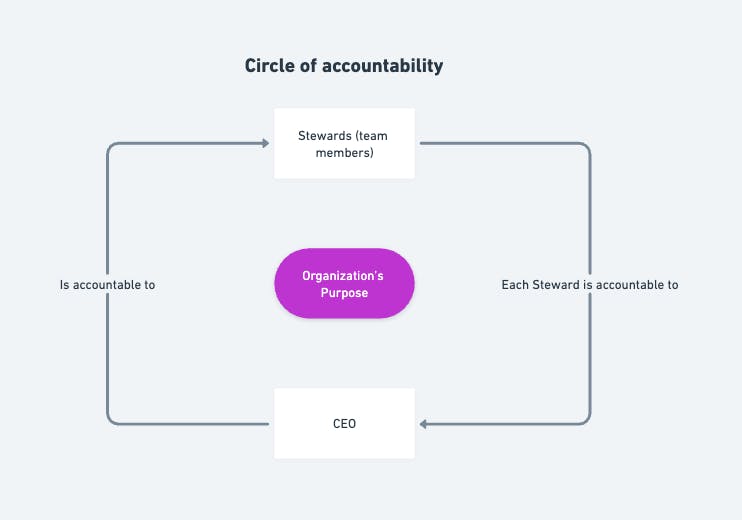

We call our design the "Circle of accountability". It's described in the diagram below.

From traditional companies, we adopt the idea that the CEO holds each team member accountable. At Sharetribe, the CEO is the only team member with the legal authority to issue an official warning or terminate a team member's employment.

From cooperatives, we adopt the idea that the CEO is accountable to the team as a collective. If the CEO starts acting in ways that are not in the best interest of the company, the stewards can ask the CEO to leave.

From steward-ownership, we adopt the separation of money and power. The Sharetribe team members can receive market salaries, and founders and early employees can receive capped "delayed compensation" from the company's eventual profits. Some team members also bought investor shares during Sharetribe's crowdfunding campaign, and they'll receive a capped return on them. The stewards can't exceed these caps, and there's no additional mechanism for them to use the company's profits for accumulating their personal wealth.

We believe that with this design, every stakeholder at Sharetribe is truly accountable for doing their best to achieve the company's purpose.

What's more, the structure is future-proof and not dependent on the role of any single person. One day, Antti and I will no longer be working at Sharetribe. Our structure provides an obvious path to continuity: if I leave, I need to give up my voting share, and the remaining stewards will choose the new CEO.

How decisions are made at Sharetribe

As said, a problem with democratic governance is that democratic decision-making is slow. In society, this is by design: changing laws should be a deliberate process that doesn’t need to be rushed. A company, though, needs to adapt more quickly to a changing environment if it wants to remain relevant.

The way we solve this is by treating voting as a last resort.

In a way, being a steward is both the most and the least important role to hold at Sharetribe. The most important, because the stewards hold the ultimate power. The least important, because in practice they might never use that formal power.

From the early days of Sharetribe, we’ve used a decision-making framework most commonly called self-management (we like to call it "co-leadership", to emphasize that team members are not only managing themselves, but the entire organization as a collective).

We don't have a formal hierarchy with supervisors and subordinates. Instead, we try to identify the right decision-maker in every situation. Usually, it's the person closest to the issue. If the decision is big and more difficult to reverse, we encourage the decision-maker to ask advice from other people close to the issue. The decision-maker doesn't need to follow the advice they get: ultimately, the decision is theirs.

If it's an issue that touches everyone at the company, anyone can make a proposal, and the agreement is reached using consent-based decision-making: if nobody blocks the proposal, it moves forward. If you block, you are responsible for working with the person who initiated the proposal to amend it so that you can both accept it.

If a conflict arises, we bring more people in to resolve it. Only in an extreme case where no resolution could be found would the CEO step in to resolve the conflict. So far, this has never happened.

These simple practices allow us to make decisions and resolve issues quickly without relying on power dynamics created by hierarchical organizational structures.

What leadership looks like at Sharetribe

I believe every organization needs leadership: the ability for an individual to influence or guide others to a specific direction. However, I also believe many traditionally-governed organizations mistake power for leadership.

A key problem for dictators is that the people close to them have a strong incentive to tell them what they want to hear—not what they need to hear. Organizations might genuinely believe they’re a meritocracy, all the while formal and informal power dynamics ensure that the “best arguments” always seem to come from those in a position of power.

At Sharetribe, we believe every team member can participate in leadership. Every individual can hold multiple different roles. In some of them, you might take the lead, while in another, you might follow someone else's leadership.

Acts of leadership are everywhere at Sharetribe. They can happen through coaching, with senior team members guiding more junior colleagues. They can happen through a team member taking ownership over an initiative: “we're doing this, I'll lead the effort, who's with me?” They can happen through facilitation, with a team member chairing a meeting, ensuring it gravitates towards a decision. They can happen through giving advice to the decision-maker.

Personally, I prefer leadership by storytelling. I believe that if I tell the best story about where we should go next, and make a convincing case for it, people will want to follow me. Because I've stripped myself of nearly all of my formal power, I can be certain that if people disagree with me, they will voice it. I find this very important.

I don’t think any organization can be entirely free from informal power dynamics. But I think our design can minimize their negative impact and maximize psychological safety, which many researchers have confirmed as one of the most essential components associated with an organization's performance.

Putting it all together

Today, Sharetribe is fully owned and controlled by its team and funded by its 1,500+ paying customers. At the time of this writing, we operate with a healthy 10%+ profit margin, and are on track for our second consecutive year of ~30% revenue growth. We’re confident that we'll be able to honor the commitments we made to our crowdfunding investors and ensure they receive the (capped) returns we promised. What's even more important, this revenue growth is fully aligned with our purpose of democratizing platform ownership.

Our day-to-day way of working and approach to decision-making are in permanent beta: they will continue to evolve. Meanwhile, the core underlying permanent structures (steward-ownership and democratic governance) will continue to hold everyone at Sharetribe accountable for doing whatever they believe is the right thing in each situation, from the perspective of our purpose.