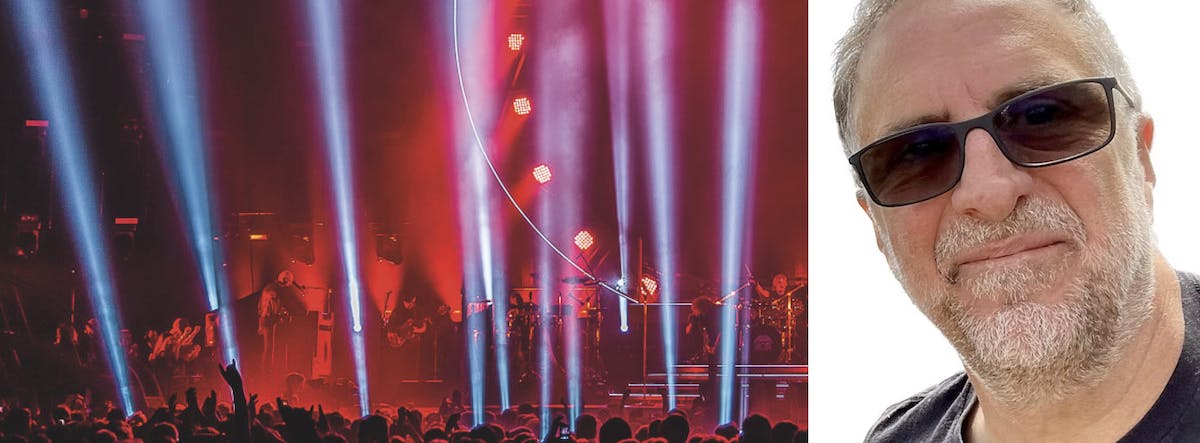

Marcel Fairbairn from GearSource

GearSource survived three re-platforms and found stability after two decades

The marketplace for professional sound and lighting equipment has been connecting buyers and sellers since 2002, long before most marketplaces existed.

"Sharetribe is unbelievably solid and reliable. That's what we needed."

– Marcel Fairbairn, founder of GearSource

Marcel Fairbairn’s journey to a marketplace founder began as a musician. Then he moved into music retail and sold professional lighting and sound systems for major artists like Madonna, Michael Jackson, and the Rolling Stones.

By 2001, Marcel had become a minority owner in a lighting brand but felt the entrepreneurial pull growing stronger. When he decided to venture out on his own, he turned to what was then an emerging frontier—the internet.

"If my next thing was going to work, it had to be on this thing they called the internet," Marcel says.

He spotted a critical problem in his industry. Lighting and sound technology quickly evolved from analog to digital, and along with it, manufacturers and distributors were accumulating warehouses full of obsolete equipment. Companies focused on selling the latest technologies and largely ignored this "invisible inventory problem".

This insight became the foundation for GearSource—a platform to help companies sell their unused audio, video, lighting, and staging equipment. Initially, Marcel focused on manufacturers and distributors and then discovered an even larger opportunity with rental companies. These businesses constantly needed to update their inventory based on artists' specifications for tours and events.

To build his first platform in 2002, Marcel used a piece of software called Actinic that came on CD-ROMs. Early operations were entirely manual: when an order came in, Marcel would enter it into QuickBooks, send a purchase order to the seller, and an invoice to the buyer.

For nearly 16 years, GearSource operated successfully without Marcel ever identifying it as a marketplace. That changed in 2018 during conversations with David Kalt, founder of Reverb (later acquired by Etsy).

"Until then, I had never called us a marketplace. I didn't know that's what we were," Marcel says.

By 2019, GearSource was running on antiquated technology, and Marcel decided it was time to find "the Shopify of marketplaces."

What followed was what he describes as "three terrible re-platforms in three years" before finally finding Sharetribe.

"We needed something very solid and very reliable. Sharetribe is a little bit like Volvo. It doesn't have a ton of crazy bells and whistles, but it's unbelievably solid and reliable," Marcel says.

Along with the platform changes came an evolution in GearSource's business model. In the early days, the company acted more as a broker, controlling the listing prices and taking an average commission of around 22%.

As the competitive landscape shifted and Marcel embraced the marketplace mindset, GearSource reduced its take rate to a blended average of about 11%.

"When we started thinking about growth in 2019, the biggest thing we did was cut our margins," Marcel explains. "Most companies look to increase their revenue, but we took our take rate down."

Today, GearSource operates with much more automation and less manual intervention, focusing on creating value for its community. The average order value hovers around $20,000, making it a challenging but rewarding business when it works well.

"It's fun to wake up on Monday morning and go, ‘wow, I just had a $200,000 weekend with orders that have taken care of themselves,’ Marcel says.

For early-stage founders, Marce’s advice is to start as lean as possible.

“Do it on the smallest budget you can possibly manage. Today, you can use AI and online tools to be a one-person organization until you reach a point of having revenue."

After weathering everything from the dot-com bubble to the COVID-19 pandemic (which temporarily made live events illegal), GearSource shows how resilient a well-run marketplace can be—even if it took its founder 16 years to realize that's what he was building.

Watch or listen to the full discussion with Marcel

You can also listen to this episode on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts. Don't forget to subscribe to be notified when new interviews drop!

Transcript

Sjoerd Handgraaf - Sharetribe: Hi, Marcel. Welcome to the podcast.

Marcel Fairbairn - GearSource: Hey, Sjoerd. Thanks for having me.

Sjoerd: I appreciate it. Thanks for making the time. It’s going to be the first-ever Sharetribe customer-focused podcast. Things might be a little bit bumpy on the way, but let’s first put some context around who you are and what we’re going to talk about with GearSource.

So could you tell us a little bit about what you did before you started GearSource?

Marcel: Yeah. First, it’s funny that you said this is the first-ever founders podcast because I believe I’m probably one of the first-ever marketplace founders who was crazy enough to get into this business. So it’s quite appropriate. People call me the OG of marketplaces because I think other than eBay and Amazon and maybe a couple other of that size, I was the only one.

I began my business life in the weirdest possible place. I was a musician, a professional musician. Well, sort of a professional musician. I was a 13-year-old musician who was a singer, and one day our manager, who was a Catholic priest, came to rehearsals and said, “Marcel, I’ve just fired our bass player and now you need to learn to play bass as well, and the next gig is in thirty days. You need to learn the instrument and 40 songs in thirty days.” Okay.

So I did that and, not too far into my career as a professional musician, I realized that I was making $200 a week and spending $250 on my bar tab. Okay. It probably wasn’t a recipe for life success and financial success.

Sjoerd: It does sound like a professional musician, though.

Marcel: It’s very true. So I pursued a life in sales and specifically music retail—guitars, instruments of all kinds—but in a rock-and-roll sort of music store, and that eventually evolved to sound and lighting systems because I realized that the AOV was much higher on a $100,000 lighting package or sound system than it was on a $500 guitar. And so you could work just as hard, but the outcome was much greater.

Eventually, I was living in Canada, Western Canada at the time, and I landed a job with a Danish manufacturer called Martin Lighting, managing sales for their North American distributor. So I had a twelve-year career that spawned into a very nice career, selling lighting for massive tours like Madonna and Michael Jackson, the Rolling Stones, the Eagles—so many really great artists. Traveling the world, getting to know people. When I first started working with Martin, I was from Western Canada. I’d only really been to Los Angeles and New York and Las Vegas for a trade show, but I didn’t really know my way around the United States, and here I am the Vice President of Sales and Marketing. So traveling the world was amazing. I got to know a lot of great people in great countries, and eventually became a minority owner in a lighting brand in 2002.

I got bored, really, and I decided to leave that company, sell out my shares, and become an entrepreneur. And it was always in my spirit, in my mind to be an entrepreneur—in my DNA—and even working for companies, I was very entrepreneurial. So I did what everybody did at that time, and maybe even a bit early for you, but I went out and bought a CD set, which was Seth Godin, and it was a really cheesy name—I think it was like “making money on the Internet” or “creating a business on the Internet” or something. And this is probably late 2001 at this point.

And I thought, you know, my next thing has to be on this thing they call the Internet, and it’s gotta be an Internet business of sorts.

And the second thing I knew was that the industry I was in was struggling with something that was related to the ramp-up of technology and how much quicker technology was moving in that industry. Lighting fixtures, sound systems were going from analog to digital, lighting systems were going into these automated lighting packages that were now advancing very quickly.

And so what I saw in this, as a guy who was running facilities to distribute these products, was that products were getting pushed further and further back on the shelf as new models came out. Imagine if you had a million iPhone 1s in stock, and the iPhone 2 comes, and you just go, "Oh, go back further on the shelf. We’re going to put the iPhone 2s in front of you.” Eventually, those iPhone 1s have no value.

So I’m listening to this Seth Godin thing. He tells this story of a hippopotamus and some special bird. The hippopotamus lays in mud, staying cool. And he lays there with his mouth open. And there’s a little bird that goes inside and lands in his mouth and eats all of the food off the hippo’s teeth. And the moral of the story is basically the hippo ends up with clean teeth. He’s happy. And the bird was fed. Really disgusting meal, but the bird’s pretty happy, right?

And so Seth’s message was that you need to create businesses on the Internet where you’re doing something that to you is your bread and butter—it’s your food—but to the customer or to the people that you’re serving, it’s nothing. It’s like literally you’re taking such a small thing from them, but to you it becomes your entire revenue. This was the spark for a marketplace.

And so what I decided was that in my industry, there was this sort of invisible inventory problem happening, and many people didn’t even recognize it. They were so focused on selling the latest, newest stuff, and they were forgetting about all this old stuff. Sales teams were incentivized to sell the new products.

My initial focus in coming up with this—and at the time I didn’t know it was called a thesis, but it was basically a thesis on marketplace—was that manufacturers and distributors were going to run into very significant problems with inventory, and there was really no way to get their sales teams focused on selling this old inventory except to just drop the price so low and then give the sales guy a big commission to sell it. But instead, I was going to come along and help them with that inventory. I was going to be ultimately 100% focused on that, either B stock, or discontinued, or even used demo stock, or whatever it was, while they focused on their new product.

Sjoerd: Had they realized that already as a problem, or were you ahead of the curve? Or were they in denial? Because I’m just thinking about—they’re expensive. They’re not digital assets of which you can just duplicate a million without cost. It must be somewhere on the P&L [profit & losses statement]. Right?

Marcel: It is, but it’s ignored. And so if your overall inventory number is 10 million and there’s a one-million-dollar problem in that ten million, we’ll focus on that next week, next month, next year, whatever. And so I think people—large enough companies that had asset managers and people who were inventory control experts—were noticing this trend. But I was running a couple of fairly large businesses—I mean, $25 million businesses—where this could really become a significant problem.

So I think it was bubbling, but it hadn’t yet reached the surface. Again, that was basically my initial thesis for a marketplace: while they were focused on selling new equipment, I was going to build a business on the Internet, because Seth Godin said so.

And also because from the very earliest time in my mind, I wanted to be a remote company. I had a place that I had built up in Canada in the mountains, and I wanted to spend time in Canada where I’m from. But I also wanted to be able to be in the Florida Keys if I wanted to as well, and nobody knew the difference. Nobody cared where I was, which meant it was a remote company very early.

Very shortly after launching—and I know we’ll get into the launch—but very shortly after, I sort of changed my direction based on outreach from a touring rental company who said, “Can you also do this service for us?” And really my focus shifted away from manufacturers as much because it was a problem there, but it was a much larger problem for rental companies who were constantly evolving their inventory.

Sjoerd: So had you already identified... because if we sort of break this down into the supply-demand part, obviously your supply is there, just sort of begging you to take it off their hands. But if they’re not selling it, if they can’t move it, who did you have in mind to move it to at that point?

Marcel: Yeah, it’s a great question. So one of the things that I learned early on is that most of those companies would not sell to their competitors. They wouldn’t go to a direct competitor and say, “Here’s a hundred of these lights that I no longer need. Would you like to buy them?” Because they’re then basically building that competitor to beat up on them.

However, they would allow me to sell them to their competitor, which is very odd. I mean, literally, I have done hundred-thousand-plus-dollar deals where a company sent a truck a block away to pick the lights up from their competitor or the sound system from their competitor and bring it back to their warehouse. It was done on a platform based thousands of miles away.

Sjoerd: So you were saying—I cut you off—you were saying that the rental industry came in, or tour rental industry came in, so you changed directions a little bit?

Marcel: My initial target for supply side was really specifically manufacturers and distributors because that’s really where I came from, and I saw the problem developing. So those businesses did support us early on, but it wasn’t big enough to really be exciting. First of all, again, they had to identify and accept that there was a problem. Then secondly, they had to be willing and prepared to allow an outside company to come in and solve that problem for them.

However, in our industry—in the sound and lighting and video rental industry, where our customers rent to performers or to festivals or to trade shows and conventions and conferences—these companies hold a huge amount of inventory, and much of the business is specification-driven, meaning someone outside is saying, “Okay, we’re going out with the Rolling Stones next month, and we want ABC light.” And the rental company might say, “Well, we have DEF light. Will that be okay?”

“No, no, I have to have ABC lights.” So now that company has to get rid of some DEF lights and go out and buy the ABC lights. And they don’t have a disposal plan. None of these companies, at least initially, in the early stages, had a disposal plan. They just knew that they had to go buy this other stuff, and they didn’t have room on the shelves for it because they already had old. And so it was a significant problem in a much larger part of the market, which was these rental companies—these large rental and production companies globally.

And so, really, we shifted focus to not necessarily our direct customers, which we thought were manufacturers and distributors, but to our customers’ customers, these rental companies. And that’s where things really took off.

Sjoerd: How did you—because this started early 2000s, you said like 2003, 2002. How did you get the first platform up and running?

Marcel: That is a crazy answer, actually. So I called the most computer-savvy person I knew, which was a friend of mine named Jamie, and I said, “Jamie”—and Jamie was in my industry—“here’s what I want to do. I want to build this platform where we’re selling product for other companies, so we don’t have any inventory, it’s not e-commerce,"—which was even early at that time as well—"we’re going to be selling from one company to another company and we don’t own any of the equipment, we never see the equipment.”

He goes, “Well, that’s a crazy business.” And I said, “Yeah, it probably is, but we’re going to try it anyway.” And so he came up with a piece of software that was actually sold on CD-ROMs. It was a company from England called Actinic. Never heard of it before. Never seen it since. We were probably the one and only package they sold.

And he built a website using this on-prem software. I had a server in my bedroom, in my house, that had this software on it. It was probably really early e-commerce software. It had nothing to do with marketplace whatsoever. But it worked. It got us off the ground, and it carried us for about two years. I think 2004 was when we launched a proprietary piece of marketplace software.

Sjoerd: That’s crazy. I mean, if I think about 2002—because I’m thinking, “Oh, yeah. Early.” But that’s ridiculous. I remember building websites at the time with Dreamweaver or just flat-out HTML, just hand-coded. I cannot even imagine if someone would have come to me—because for some people in my network, I was the computer-savvy guy—“Hey. I need this platform.” There’s just not even a reference out there.

Marcel: It was wild. And I’ll tell you, when it was working, nothing was automated. I mean, literally, all it would do is go “ding, you got an order,” and we’d have to go take that order—me—put it in QuickBooks, and from QuickBooks we would send a purchase order to the seller and an invoice to the buyer, and we’d collect the money and pay it to the seller and the seller would ship to the buyer. It was crazy how complicated the business was, but remarkably simple too in a sense.

Sjoerd: So this was 2004—you had already shifted to the rental direction?

Marcel: By the end of the year in 2002, we had already a company out of Chicago, which is one of the largest touring lighting companies in the world, called Upstaging. They tour with the Stones and U2 and Madonna and all these big acts. They were good friends of mine, and they saw a couple of press releases and people talking on the Internet. “There’s this new website called GearSource.” John Huddleston, who ran that company, called me up and said, “Hey Marcel, is this something that you could also do for our company?” And I went, “I guess so. Let me work that out for you.”

And it really was the same business. It was literally no different. It was just us widening our thoughts on supply to include what now is probably 90% of our supply: the rental and production side of the business.

Sjoerd: Did you have to—so 2004, you launched your own proprietary platform?

Marcel: Yes.

Sjoerd: Did you make any changes otherwise, like in the business? Because you said now it’s evolved to 90% rental businesses. Maybe you can talk us a little bit through the development of the business, in terms of changes of customers, or is it just directional growth along the same path?

Marcel: Pretty much. It was kind of linear growth, the exact same customer types, just connecting more of them together. More buyers, more sellers. We got a bit of a network effect going, but it was quite organic.

Since the very beginning, we’ve never done any advertising. First of all, there were no Meta ads or Google ads back then yet. But even when that existed—when AdWords became a big thing, and then eventually Facebook advertising—we still didn’t do that. Actually, our very first digital ads started in 2024. That’s when we started advertising.

Sjoerd: So 2024, the first advertisement. But at what point—you mentioned you introed your story saying about the Seth Godin book and you want to build this business. At what point did you realize that, “Oh, yeah. This is going where I want it to go. This has momentum or potential”?

Marcel: Yeah, it’s a great question because actually, I was very cognizant of that. Although I was very entrepreneurial from a mindset standpoint, physically, as far as paychecks, I was collecting a paycheck my entire career thus far. It was quite a leap of faith going from collecting a fairly hefty paycheck at the time to no paycheck whatsoever and spending my own money to build this thing. Because I never thought of investors. I didn’t know of any such thing as a VC. I had no idea that you could get other people to pay for your business startup.

So I just said, okay, well, if I’m going to build this, I gotta scrape up some cash. And my now ex-wife at the time—I had a conversation with her and I said, “I’m going to take a second mortgage on our house. Plus I’m going to take pretty much all the money in our savings account, and I’m going to go all in on building this little company.”

And she goes, “Okay. When might we consider that that’s going to turn into something?” She was also in the music business. She worked for record companies. And I said, “Okay, well, here’s my plan: at six months, I’m going to stop and I’m going to take a good look at the business. How’s it doing? Does it have a future?” And so at six months I did that, and by then we already had some pretty good momentum. We were making money. So then I said, “Okay, in six more months—twelve months from starting the company—I want to have replaced my paycheck, my previous paycheck.”

Now this was a big goal. This was, in 2002, I don’t know, $15,000 a month or something, maybe a little more than that. So I said, “I want to replace my paycheck in another six months.” And I sat down in six months—I had just started taking a paycheck that was good enough. And so I said, “Okay. We’ve got something here.” And I’ve never looked back since. It was a journey.

Sjoerd: Have you changed anything in your revenue model? Because again, you didn’t really have any examples. How did you monetize?

Marcel: Well, right from the beginning, it was basically a commission or fee-based system. But in the beginning, we were managing the listing—the seller wasn’t managing the listing. So we were controlling the price. If he told us he wanted $1,000, we would make it $1,100, $1,200, $1,500—whatever we thought the market would bear—and then we’d pay him his thousand. I think our average take was around 22% in the beginning. For most of our existence, it was around 18 or 19%.

And then when you talk about evolution—most companies look to increase their revenue. When we started thinking about growth, which was 2019 is when I really said, “Okay, we’ve got something here. First of all, we need to replatform, but second, we really need to start focusing on growth.”

The biggest thing we did is we cut our margins. And so we took our take rate down to what is now a blended average of about 11%, but our lowest take rate is 7% to very large, very frequent sellers. And it was because obviously the competitive landscape shifted throughout the journey.

Sjoerd: Could you talk me a little bit through that thinking? Because I think this is really interesting also for founders listening—how to monetize, and then if you were enjoying a particular take, what was the impetus for making that change? You said the landscape has changed, but realistically, what happened, and what is the consideration there?

Marcel: Yeah, it’s a great question because there was actually an event that happened. We were in talks with a marketplace founder of a company called Reverb in 2017 going into 2018, right before they sold. Those talks went very quiet at one point and I didn’t know why. I was like, what just happened here? Then a month later I got a call from the founder, David Kalt, who said, “Yeah Marcel, I’m sorry I ghosted you, but we sold to Etsy.”

I guess that’s a good reason for ghosting me. That’s okay.

Sjoerd: Fair enough.

Marcel: I wasn’t upset because David Kalt gave me a very good lesson. He gave me a beatdown on our first call, really. First of all, he said, “I love your business because you’ve managed to go far upmarket from where Reverb is. Reverb sells guitars and amplifiers and drums and instruments, and we sell sound systems, but mostly low-end—really inexpensive, like for DJs or churches. You’re selling million-dollar sound systems and you’re selling them to other countries. You’ve done something we haven’t managed to do, and I’m curious.”

By the end of that call, his advice to me was two things. One is, “It’s really hard to invest in a business that doesn’t have a tech cofounder. You’re not fully committed to being a marketplace unless you have that.” And I’m not slamming David Kalt—he’s a very successful man—but I disagree with him on this. And Sharetribe wouldn’t exist if he was correct. If he was right and your cofounder had to be a product guy or girl, Sharetribe and other marketplace platforms wouldn’t exist.

But the thing that he did tell me that was accurate is we were far too high-touch, and it was going to be impossible to scale the business to where we wanted to be and where we should be unless we became a lower-touch company. And I knew exactly what he meant because I was struggling with the same concept, which is we’re handholding every customer, we’re handholding every deal, we’re actively involved in absolutely every sale we make, whether it’s a hundred dollars or a hundred thousand dollars. That was a pivotal discussion.

Actually, one of the things he taught me is that we were a marketplace. Until then, I had never called us a marketplace. I didn’t know that that’s what we were.

I mean, we had taglines like “connecting buyers and sellers globally,” but that never became in my brain marketplace—no one ever said, “Hey, do you realize you’re actually a marketplace?”

And so in 2018 or ’19, we started calling ourselves a marketplace. And then, you know the story, the plot thickens, and basically we did our first of three replatforms in 2020. We did three.

Nobody does this in the marketplace community. And for anyone listening, please never do this. Please. I’m telling you now, people at home, do not do this. We replatformed three times in three and a half years. They’re all terrible stories.

But the first one wasn’t. The first one basically took us from—going backwards a little bit—in 2004, when we finally built our own platform, it was built on ColdFusion. Do you even know what that is?

Sjoerd: No. I feel I’m quite in touch with older technologies. This is not one of them.

Marcel: Yeah. ColdFusion. I think the only people on earth who still have any ColdFusion product are the government. There are so few coders in the world who know anything about ColdFusion anymore. We probably had one of the last ones on our staff and literally he didn’t build anything. He just kept it from eating itself and imploding.

And so we were on ColdFusion for almost fifteen years. In 2019, we decided it was about time to get off of ColdFusion.

And so I said, “I’m going to go out and try and find the Shopify of marketplace and see if there’s a platform out there, because I don’t want to build. I want to buy. I want to rent.” We didn’t find Sharetribe for some reason.

Sjoerd: I take that personally.

Marcel: It was 2019, so it was early for you guys as well. And probably too early. It would have been too early for us, I think. I think you were more of a smaller enthusiast marketplace platform more than—because we were pretty enterprise-y, you know?

The best thing we could find was a combination of WooCommerce and Dokan. And for those who don’t know, Dokan is a plugin from India. We were one of their first customers, and it takes WooCommerce and makes it into a multi-vendor marketplace piece of software.

So we hired a developer, an outside developer, to rebuild basically GearSource onto this combination of software—WooCommerce and Dokan.

Sjoerd: Isn’t WooCommerce—doesn’t that require WordPress? So it's like WordPress on which you build Commerce, on which you then have Dokan.

Marcel: Yeah. The team of developers who I hired did a bunch of research and decided that this was going to work. They basically checked all the boxes. On this side was needs, on this side was things that it offered. And it checked most of the boxes that we needed.

Everyone says I was in the worst business for COVID. We were in the worst business for COVID. Live events—forget it. It was illegal to have a live event. We were in by far the worst business. I can’t think of one that’s worse than live events. So all of our customers were at zero revenue. Some of them eventually went to these virtual studios and virtual performances and stuff, but it wasn’t generating any cash, not enough to be a real company.

So one, it was a great time to build a platform because you had time—there was nothing else to do. But obviously, it was a heavy financial drain on a company that wasn’t making any money throughout 2020.

So we launched in September of 2020. And again, either the best or worst time to launch a business is when you have very few customers. But we did have an audience because people were sitting at home. They didn’t really have anything to do. They weren’t working.

We were able to get it working. It launched, I think, in September of 2020, and one of the people who helped us get it launched was Dan Melnik, who was one of the architects of Reverb. He was the COO at Reverb before they sold and a very smart guy. He helped us.

Because it was not easy. The Dokan guys at the time were impossible to deal with, WooCommerce was not easy, WordPress was not easy. It really was the wrong platform for us.

But we got it launched, and I’ll tell you what it did for us—and this is going back to your original question—it convinced us that not only could we automate a lot of things and take ourselves out of the loop on a lot of things, but that we could lower our margin and lower our take rate and put us in a much more marketplace-y place.

And so the WooCommerce platform and my conversations with David Kalt took us from behaving like sort of a buy/sell company that happened to be selling other people’s inventory to being a real marketplace.

Sjoerd: That’s so interesting because we have that as a—like, in the marketing team, we have that as one of the theses: there are actually loads of marketplaces out there who do not see themselves as a marketplace business. We always give the example of secondhand fashion—they go look for business advice in fashion business. There are lots of people who do not have the realization that, oh, actually, 80% you’re more like a marketplace and only 20% of your special sauce is the fashion part. That’s just mind-blowing that you’ve done that for so long. Not that it really has hampered you, but it just opens a whole new perspective to how to run the business.

Marcel: Completely changed my mindset. That was significant, and I’m very grateful to David Kalt, even though he didn’t end up buying our company. I didn’t really want to sell anyways, but I’m very grateful to him for giving me that education and a wake-up call. It just changed everything about the way I thought and down to where today, we’ve even changed our hiring and the types of people that we’re after for the company.

We’re a marketplace company now. We’re not a lighting or a sound or a video company. We’re a marketplace company that could be selling automotive parts, or it could be selling sound and lighting equipment. It was a great education.

If I can continue just for a moment longer on the WooCommerce thing. Our industry opened up again basically late 2021, because again—worst industry—we were the last one to come back.

Our WooCommerce site just again started eating itself. We had a full-time developer just keeping it from crashing. We were always at like 99.9% of server use. It was unbelievably unreliable and horrible. Most of the features that were supposed to work didn’t work. It was impossible to build on top of because it was so buggy.

It was just nasty, but it worked as a marketplace. It got us to behave like a marketplace. For the first time we had Stripe. For a long time, people were paying us either by check or by wire transfer or by credit card, and then we were paying sellers either by check or by wire transfer. I haven’t written a check since, I think, 2020.

It really evolved my thought process and my way of thinking, which then evolved the processes and the systems and methods for how we did what we did. That continued on a journey where we had one stopover in the middle, which I won’t talk about much, but another Sharetribe competitor, where it was a complete disaster.

So we were only on that platform for about nine or ten months, and had to build another one, which at that time was Sharetribe.

Sjoerd: I mean, we’re obviously very happy to have you, and I think you’re definitely the anomaly here, because if you go to sharetribe.com, it says “for founders,” and our positioning is indeed very much towards helping someone get a marketplace off the ground who’s just starting. I think we’re getting there also through projects like with you—towards this situation where migrating becomes much more intuitive or much more fluent.

Also because of similar realization on our side that for us it’s also a part of the market that we’re currently not talking to. There are loads of marketplaces out there who might—despite your own terrible experiences with WordPress or the other competitor—there are people for whom this works or who think that this is as good as it gets. And so we’d be happy to be able to show them also a better alternative, so to speak.

What’s the number one feature that you’re most happy with that you’ve built now with us that you couldn’t build in the other situations?

Marcel: I wouldn’t say it’s a feature. I would say it’s just an overall thing, which is reliability. There was a show with Dudley Moore in it where he was an advertising executive, and he went crazy and he could only tell the truth. He made an ad for Volvo, and he said, “Volvo: boxy but good.”

And to me, Sharetribe is a little bit like Volvo. It doesn’t have a ton of crazy bells and whistles, and it doesn’t have the most sexy features you’re ever going to see in a platform, but it’s unbelievably solid and reliable.

And that’s what we needed at that point, because remember, by now this was going to be our fourth platform in four years. It needed to be very solid, very reliable. We went through a “has and doesn’t have” sort of list with Journey Horizon, who was one of the developers that we met through Sharetribe.

We knew what we were getting into as far as the didn’t-haves, which—nothing too tragic as far as our platform was concerned. And the things that it did have were very, very good.

For us, it’s been very pleasant. It’s almost like if you had three really bad girlfriends in a row or something, the fourth one— all of a sudden, you’re two years into it, and you’re going, “I really still like this girl.” And that’s where I’m at with Sharetribe.

Sjoerd: Happy to hear it. Also happy to take the Volvo reference. They're from Sweden—they’re on the other side of the pond where we are in Finland—so I think that’s an appropriate metaphor. I’ll take that.

In a way, you are a very recent marketplace founder, because you’ve only recently realized you’re a marketplace. Is there any advice that you have for early Sharetribe customers—this is going to go out to our mailings, to our customers, many of them very early stages. What would you give as advice for people who are starting a marketplace—do this or maybe don’t do this?

Marcel: It’s such a fantastic but loaded question. I have been operating a marketplace since 2002. I’m a unique individual. I’ve been bruised and beaten up, and I’ve made every mistake possible, which is sometimes more important than just talking to the most successful marketplace owner in the world.I’ve survived twenty-two years, which—tell me another marketplace outside of eBay and Amazon who have done that—I can’t think of one.

So first and foremost, whatever it is that you’re going to be a marketplace for—whatever that product is—do research and make sure that there is a market. Make sure that there is a supply side and that there is demand for it. I get invited a lot to these dinners or talks or groups with marketplace startups, and they’ll say, “Here’s what my marketplace is,” and they’re very passionate and very excited. I haven’t got the heart usually to tell them, “That is a terrible business idea. That’s just not going to work."

And the reason I know that it’s not going to work is my AOV—my average order—is around $20,000. It’s a hard business with a $20,000 AOV. I can’t imagine what it’s like when your AOV is $3, and a lot of startups are starting marketplaces based on sub-$100 AOV. You have to be so efficient, and generally efficiency, I find, comes with scale. It’s hard to be really efficient when you have two or three employees, and you have all of those expenses.

So the first thing I would say is really vet the market, make sure that there is a market, make sure that there’s a need for the product that you’re creating—just like any other business. I know that’s an incredibly obvious answer, but I believe it’s underutilized: really vet the need.

And then from there, do it on the smallest budget you can possibly do. Go out and build a business where it’s you as the only employee to begin with.

And today it’s so easy to do that. Twenty-two years ago it wasn’t. Today you can use AI, you have online everything—like I didn’t even have QuickBooks Online in the beginning, I had it on disks because it didn’t exist online yet. Today, between AI and all of the different online tools and inexpensive applications, it’s so easy to be a one-person organization and build a marketplace that gets you at least to a point of having revenue.

And then from there, be very conservative with your growth of expenses—be aggressive on your growth of revenue, but very conservative on growing expenses. That’s not what I see in most marketplaces. I see they raise a million dollars, they go out and spend $2M, and then they wonder why they’re bankrupt.

A marketplace is a tough business to succeed in, but it’s a great one when you get it to go and you’ve got network effects and that hamster wheel running. It’s an unbelievable business.

It’s fun to wake up on Monday morning with orders that have taken care of themselves over the weekend, and you’re like, “Wow. That was fun. That’s great. I had a $200,000 weekend, and all I did was play golf." I don’t play golf, but—

Sjoerd: I get it. Thanks, Marcel. And let’s end on that. I think that’s fantastic advice. Some of the best advice we can’t repeat enough, so it's more than welcome. I want to thank you a lot for your time.

Read more founder stories

› Gritty In Pink launched and saw sixteen months of continuous growth

› Drive lah raised millions in venture capital and scaled internationally

› socialbnb, a marketplace for responsible travel alternatives, is reimagining tourism

Start your 14-day free trial

Create a marketplace today!

- Launch quickly, without coding

- Extend infinitely

- Scale to any size

No credit card required